Rescue Ready: How to Develop a Confined Space Rescue Plan That Works

A practical guide for Ontario workplaces, beyond compliance, into real‑world readiness

Confined spaces are dangerous not just because of what’s inside, but because of how limited access, poor ventilation, and unpredictable conditions combine to create high-risk environments. A toxic atmosphere, a sudden engulfment, or a fall can turn routine work into an emergency, and without a well-developed rescue plan, lives are at stake.

Ontario’s Confined Spaces Regulation (O. Reg. 632/05) under the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) mandates written rescue procedures before any worker enters a confined space and requires that trained personnel and appropriate rescue equipment be available to implement those procedures immediately.

But simply having a piece of paper labeled “Rescue Plan” isn’t enough. A good rescue plan must be clear, functional, tailored to specific risks, and tested regularly.

In this post, we break down the steps to develop an effective confined space rescue plan, legally compliant in Ontario and built for real emergencies.

1. Understand the Regulatory Foundation

Ontario Regulation 632/05 defines confined spaces and sets specific obligations:

Written on‑site rescue procedures must be developed and ready for immediate implementation before entry.

Rescue personnel must be trained in the on‑site procedures, first aid, CPR, and the use of rescue equipment.

Appropriate rescue equipment must be accessible and maintained.

Methods of communication must be established.

Failing to meet these requirements can lead to orders, stop work notices, or prosecution — especially if an incident occurs.

You can access the Confined Space Regulation here:

👉 https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/050632

CSA Z1006: A Best-Practice Standard You Should Know

In addition to legal obligations, it’s wise to align your program with CSA Z1006: Management of Work in Confined Spaces. This voluntary Canadian standard complements OHSA by offering detailed best practices for identifying confined spaces, assessing risk, training workers, and, crucially, developing rescue procedures.

CSA Z1006 includes:

Guidance on conducting hazard assessments and entry permits

Criteria for rescue team selection, training, and competency

Requirements for rescue practice exercises

Recommendations for equipment and communications planning

Insights on contractor management and third-party rescues

While the CSA standard is not itself law, courts often consider it during investigations and prosecutions to evaluate due diligence. If you’re building or overhauling a confined space program, having a copy of Z1006 on hand is a smart move, especially if you’re in charge of safety or compliance.

You can purchase or access it through:

👉 CSA Group: https://www.csagroup.org/store/product/CSA_Z1006%3A23/

2. Conduct a Thorough Hazard Assessment (Before You Write the Rescue Plan)

Before developing any confined space rescue plan, you need to know exactly what you’re planning for. That means conducting a task-specific, space-specific hazard assessment, not relying on general assumptions or boilerplate checklists.

Understand: What Are You Rescuing From?

Hazards in confined spaces vary widely. Your assessment must clearly identify and document the full range of potential hazards related to both the space and the task to be performed. Start by examining:

Atmospheric Hazards:

Oxygen deficiency or enrichment

Flammable gases or vapours

Toxic substances (e.g., H₂S, CO, cleaning solvents)

Potential for sudden atmospheric change (e.g., welding, chemical reactions)

Physical Hazards:

Engulfment by material (e.g., grain, sawdust, liquids)

Mechanical entrapment (e.g., moving parts, augers, rotating equipment)

Electrical hazards or stored energy

Elevated temperatures or extremes in humidity

Configuration Hazards:

Limited access or egress

Vertical entries or obstructed exits

Distance from rescue team or emergency services

Work-Specific Hazards:

Introduction of new equipment, tools, or substances

Tasks like hot work, cleaning, or component removal

Lone worker scenarios or communications issues

Use the Flowchart to Guide Control Selection

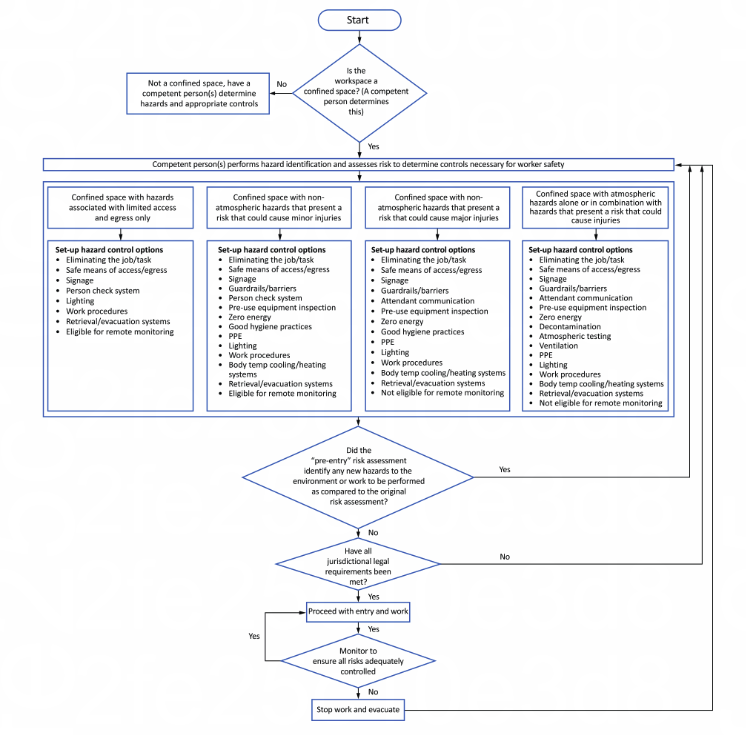

The hazard assessment must directly inform your rescue planning. To help structure this process, we recommend using the flowchart below, adapted from regulatory guidance and best practices

Source: Figure A.1 from CSA Z1006

This tool shows how a competent person classifies the confined space based on hazard type (e.g., atmospheric, non-atmospheric, or limited access) and selects appropriate control measures from options such as:

Pre-use equipment inspection

Ventilation and atmospheric monitoring

Guardrails and zero-energy protocols

Retrieval systems and body temp regulation

PPE and communication protocols

It also reinforces a critical practice often overlooked:

Reassess hazards before entry every time.

Even if the space was previously deemed low-risk, new tools, processes, or environmental conditions can reintroduce serious dangers.

3. Assign Roles and Responsibilities

A rescue plan is only as good as the people executing it. A complete plan should clearly define:

Rescue Team Members

Individuals trained and equipped to perform confined space rescue. They must be available before entry is made.

Entry Attendants

Personnel who stay outside the space, maintain communication, monitor conditions, and initiate the rescue if needed.

Entrants

The workers actually inside the space who must understand the rescue plan, signals, and procedures.

Communication Coordinator

A person responsible for maintaining reliable communication (radios, signal systems, etc.) and activating emergency services if internal rescue efforts fail.

Each individual should have documented training, understanding of their role, and a clear line of authority during a rescue event.

4. Choose and Inspect Rescue Equipment

Ontario law requires that rescue equipment be appropriate for the hazards identified and readily available.

Essential items may include:

Full‑body harnesses and retrieval lines

Tripod/anchor systems for vertical entry

Air monitoring devices

Supplied‑air respirators or SCBA for unknown or IDLH atmospheres

Stretchers or spinal boards

First aid and stabilization tools

The rescue plan should document:

Where equipment is stored

Who inspects it

Inspection frequency and records

Manufacturer’s instructions and training requirements

Inspection Records: Equipment must be inspected and maintained by a competent person, and records should be written.

5. Write the Rescue Procedures

Your rescue plan should be written, specific, and actionable. A generic plan won’t work in an emergency.

Key elements to include:

Pre‑Entry Activation

Who must be present before entry can begin?

Rescue Initiation Protocol

Clear criteria and methods for triggering a rescue (e.g., loss of communication, entrant in distress, alarm activation).

Step‑by‑Step Rescue Actions

Include roles, location of equipment, sequence of actions, and contingency options.

External Support Coordination

When and how to involve fire services or EMS.

Communication Methods

Radios, hand signals, phone lines, back‑up plans.

This plan must be ready for immediate implementation and synchronized with your confined space entry procedures.

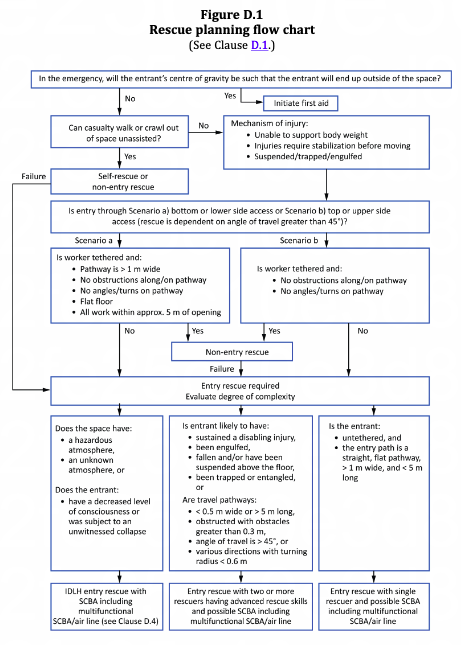

The below flow chart from CSA Z1006 provides some insight on how rescue planning can be determined.

Source: Figure D.1 from CSA Z1006

6. Train and Certify Your Rescue Team

Regulation requires rescue personnel to be trained in:

The rescue procedures in your plan

First aid and CPR

Use of rescue equipment specific to your space and hazards

Training should be documented and refresher sessions scheduled regularly… not just a single classroom session.

If your team lacks the capability to perform a timely and effective rescue, consider partnering with a professional rescue service or third‑party rescue provider.

7. Test and Practice Your Plan

A written rescue plan that has never been tested is a piece of paper… not a safety tool.

Industry best practice (and guidance from CSA Z1006, the voluntary Canadian confined space standard) recommends:

Bi‑annual practice drills

Scenario‑based exercises that include:

Rescue deployment

Communication failure

Equipment challenges

External emergency services coordination

Even where Ontario regulation doesn’t mandate specific frequencies, testing prior to entry and at regular intervals ensures the plan works under stress.

Simulated drills help identify:

Gaps in equipment or training

Delays in communication

Misunderstood roles

Physical obstacles not seen in desktop planning

8. Audit, Review, and Improve

A rescue plan isn’t “set and forget.” Build review triggers into your safety management system:

After every confined space entry

Following a near miss or incident

After equipment changes

At least annually

Review documentation, training records, drill outcomes, and feedback from rescue team members and entrants.

This is part of your due diligence, showing that your rescue plan is living, regularly updated, and verified through testing.

Rescue Planning Saves Lives, Not Just Compliance

Under Ontario’s Confined Spaces Regulation, you must have written rescue procedures, trained personnel, and suitable equipment before workers enter a confined space.

But true preparedness goes beyond compliance. A rescue plan that is tailored, practiced, and continually improved is the difference between a controlled response and a preventable tragedy.

If you need help developing, evaluating, or testing your confined space rescue plan — from risk assessment to first drill , SparksPro can help.

📩 Book a free consultation or policy review today — because being prepared isn’t expensive; being unprepared is.